Your Thanksgiving Turkey Is a Quintessentially American Bird: An Immigrant

The turkeys common on U.S. tables descended from a Mexican species and were originally bred for Maya rituals states the publication by Smithsonian Magazine, 24/11/2015

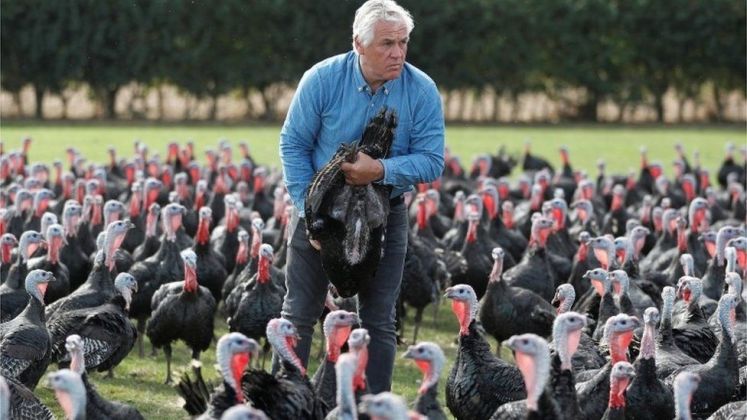

This week Thanksgiving tables across the USA will be laden with the turkey.

Two Indiana turkeys – one named Peanut Butter, the other named Jelly – were pardoned by the president on Friday. https://t.co/B49DCoHqfD pic.twitter.com/lOP1gLBWL1

— USA TODAY (@USATODAY) November 21, 2021

How turkey became a «national bird»?

There is perhaps no better known document in American history than the July 4, 1776 Declaration of Independence. Most Americans, however, do not know that it is the country’s first foreign policy document.

While the Declaration did serve to inform the American people of the colonies’ determination to form a separate and independent nation from Great Britain, it was, as John Adams later wrote, “…a formal and solemn announcement to the world, that the colonies had ceased to be dependent communities, and become free and independent States.” This formal proclamation demonstrated globally that this “rebellion” was no civil war between Britons; rather, it was a pronouncement that the United States intended to join and engage with the world as an equal, sovereign nation. American leaders quickly sent copies to European nations and it was translated into many languages and widely distributed.

Members of the Continental Congress also recognized that the new nation needed a formal seal to affix on official documents and passed a resolution on July 4, 1776 before adjourning.

Resolved, that Dr. Franklin, Mr. J. Adams and Mr. Jefferson, be a committee, to bring in a device for a seal for the United States of America.

In an August 14, 1776 letter to his wife Abigail, John Adams recounted some of the debate.

Benjamin Franklin, Adams wrote, suggested “Moses lifting up his wand, and dividing the Red Sea, and Pharoah, in his chariot overwhelmed with the waters,” and the following motto, “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

Thomas Jefferson imagined Americans as “the children of Israel in the wilderness…led by a pillar of fire by night,” alongside representations of early Britons “whose political principles and form of government” the United States assumed.

Adams concentrated on Hercules, the mythical figure of strength, “resting on his club,” gazing towards a figure of virtue, and impervious to sloth and vice.

While the Committee selected the scene from the Book of Exodus for the reverse of the seal, the Continental Congress was not impressed and tabled the concept.

Not until 1782 was the Great Seal of the United States, with a bald eagle as its centerpiece, approved.

In 1782, after six years and three committees, the Continental Congress decided on a less abstract seal and incorporated a design that reflected the beliefs and values that the Founding Fathers ascribed to the new nation.

Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress, designed the 1782 seal to symbolize our country’s strength, unity, and independence.

The olive branch and the arrows held in the eagle’s talons denote the power of peace and war.

The eagle always casts its gaze toward the olive branch signifying that our nation desires to pursue peace but stands ready to defend itself.

The shield, or escutcheon, is “born on the breast of an American Eagle without any other supporters to denote that the United States of America ought to rely on their own Virtue,” Thomson explained in his original report.

The Great Seal of the United States is a unique symbol of our country and national identity. Only one authorized Great Seal is in official use and is operated by the U.S. Department of State. The Great Seal is impressed upon official documents such as treaties and commissions.

There is perhaps no better known document in American history than the July 4, 1776 Declaration of Independence. Most Americans, however, do not know that it is the country’s first foreign policy document.

The seal shares symbolism with the colors of the American flag. In addition, the number 13 — denoting the 13 original states — is represented in the bundle of arrows, the stripes of the shield, and the stars of the constellation.

The constellation of stars symbolizes a new nation taking its place among other sovereign states.

The motto “E Pluribus Unum” emblazoned across the scroll and clenched in the eagle’s beak expresses the union of the 13 States.

Today the Secretary of State is the custodian of our national symbol, the Great Seal of the United States. The seal is impressed upon documents such as treaties and commissions, and it is also found on documents such as U.S. passports and the reverse of the $1 bill.

The story about Benjamin Franklin wanting the National Bird to be a turkey is just a myth.

This false story began as a result of a letter Franklin wrote to his daughter criticizing the original eagle design for the Great Seal, saying that it looked more like a turkey.

In the letter, Franklin wrote:

“For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country,” he wrote. The Founding Father argued that the eagle was “a bird of bad moral Character” that “does not get his living honestly” because it steals food from the fishing hawk and is “too lazy to fish for himself.”

About the turkey, Franklin wrote that in comparison to the bald eagle, the turkey is “a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America…He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage.” So although Benjamin Franklin defended the honor of the turkey against the bald eagle, he did not propose its becoming one of America’s most important symbols.

Franklin never made his views public, and when the chance had been given to him to officially propose a symbol for the United States eight years earlier, his idea was biblical, not avian.

Some scientists say , these are essentially Mexican birds, arrived in the U.S. by way of Europe.

That means by the time of Plymoth’s 1621 Thanksgiving feast, turkeys had been familiar to Europeans for more than a century.

In a strange twist of global commerce, human immigrants headed to the Americas brought the originally Mexican birds with them back across the Atlantic.

A 2012 DNA study found that the turkey genome is much less diverse than that of other livestock animals like chickens or pigs. The study compared genes from seven commercial breeds, three heritage varieties and some South Mexico wild turkeys found in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, gathered in Chihuahua, Mexico back in 1899.

The study says, All commercial turkey lines descend from the South Mexican turkey (Meleagris gallopavo gallopavo) indigenous to Mexico, first domesticated in 800 BC.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, 24/11/2015, The Franklin Institute, BMC Genomics (2012), website of the National Museum of American Diplomacy